“Oh, and by the way,” is one of those love/hate phrases for me. It often comes just after I have accepted an assignment from someone, and right before he high-tails it out of the room in fear of my response.

“Oh, and by the way,” is one of those love/hate phrases for me. It often comes just after I have accepted an assignment from someone, and right before he high-tails it out of the room in fear of my response.

Boss: “Joe, I’d like you build me a device that will allow a giraffe to fly.”

Joe: “Um, ok.”

Boss: “Oh, and by they way, you can’t use any known methods of flying.”

While it feels like a Dilbert strip in the making, I’ll show you how these seemingly unreasonable qualifiers have led to some great breakthroughs in thinking. I’ll also give you a tool you can use to help your thinking as well.

Most innovators will tell you they love constraints. Constraints are the boundaries that force us to break through our common hip-pocket answers to a problem. They force us down paths that seem downright silly at times. It is this love of constraints that makes me cringe when I hear someone say “think outside the box”. No, no, no. I want to be in the box, and make it tighter please. It’s along those constraining edges and corners where others give up and I win.

All of us benefit and suffer from a condition called path dependence. Our ability to create the future is largely dictated by where we are now and where we have been. For instance, the reason we put a period inside the quotation mark is not because it makes sense grammatically. No, we place it there because the physical constraints of the original printing presses would cause the fragile period to break when it was moved. The key to path dependency is that we get stuck designing the future because we  overestimate our reliance on the past. Have you ever wondered why the LED light bulb replacements needed to keep looking like the old, large and clunky incandescent shapes when the LED is a fraction of the size? Path dependence.

overestimate our reliance on the past. Have you ever wondered why the LED light bulb replacements needed to keep looking like the old, large and clunky incandescent shapes when the LED is a fraction of the size? Path dependence.

Our minds are conditioned to be path dependent because that is the way most of software development operates. The next release is always additive – you start with the assumption that everything that was in the previous release carries forward as baggage for the next release. Soon, every one of our designs carries this faulty logic with it. We never challenge the historical constraints. It is foreign to us to disrupt ourselves.

To correct for this condition, we must solve problems as Einstein requested, by thinking at a different level than that which got us here.

For breaking path dependence, I’m fond of a method introduced by Adam Morgan, author of A Beautiful Constraint, that he calls the propelling question.

A propelling question is a single question that always has two parts – a bold ambition combined with a significant constraint. “Could I build a rocket ship to carry satellites? Oh, and by the way, I can only afford one, so we’ll need to reuse it.” “Could I build a a neonatal incubator that normally costs $20,000 to help in impoverished areas of India for 1/100th of the  price?” (They did – and for $25! Check it out)

price?” (They did – and for $25! Check it out)

A propelling question is powerful because it doesn’t allow you to answer it the way you have answered previous questions. It forces you to take a different path to get to the solution. This breaks the path dependence. It will also frustrate the heck out of you.

Morgan tells the story of Scott Keogh, CEO of Audi America, and how he used a powerful propelling question to achieve greatness. Keogh was continually battling other car manufacturers in trying to win the prestigious 24-hour Le Mans race. Prior to 2006, the question was pretty much the same for all manufacturers,

“How could we build a faster car?”

Keogh’s chief engineer decided to change the challenge and proposed a different question,

“How could we win Le Mans if our car could go no faster than anyone else’s?”

Now that was a bold ambition combined with a significant constraint. The answer led to using diesel fuel. The car wasn’t any faster, but it had much better fuel efficiency, which led to fewer pit stops. Changing to diesel allowed the Audi R10 TDO to capture first place for the next three years – all because of a propelling question.

Keogh’s engineer made a keen observation. He had realized that they were placing a non-value creating constraint into his bold ambition. The true goal wasn’t to be faster than the rest – it was to win the race. Choosing the wrong goal limited the options available. Choosing the correct ambition is critical in developing a solid propelling question.

When you create your bold ambition, make sure the destination is truly what you are aiming for and not some path dependent choice you made based on what you know at that moment. If your goal is to create a great bill paying experience for someone on the go, don’t call it a bill paying app. Don’t even assume it will be on a phone. If the goal is remote access on the go, an app isn’t the only solution. We only migrate to the phone app because of our path dependence. What if your solution could be designed so that there was no app at all but rather used features of all the other apps a user was already using.

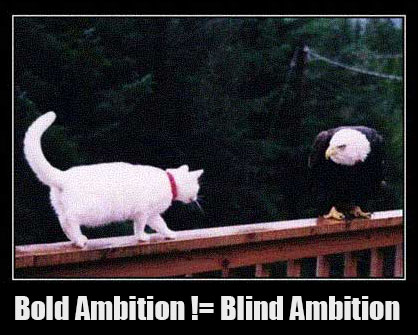

Be careful that when you attempt to create your propelling question that you don’t confuse propelling question with hard question. They are quite different. “How do I get 15% more users by the end of the year?” is a hard question. It states a bold ambition but doesn’t contain a path breaking constraint. “How do I get 15% more users while spending no engineering or marketing dollars?” would be a propelling question.

Be careful that when you attempt to create your propelling question that you don’t confuse propelling question with hard question. They are quite different. “How do I get 15% more users by the end of the year?” is a hard question. It states a bold ambition but doesn’t contain a path breaking constraint. “How do I get 15% more users while spending no engineering or marketing dollars?” would be a propelling question.

To craft a good propelling question, it is best if the bold ambition feels at odds with the significant constraint – almost paradoxical. “Build me a mobile bill paying app where I don’t have to build an app.” This tension is what takes you out of your comfort zone and forces you into a land that you have likely never experienced. This tension will cause you to reassess what you know and throw away things that you are comfortable using. You have become McGyver.

One of the coolest things about a propelling question is that if you have created and solved a good one, it is highly unlikely that anyone else has accomplished the same, if for no other reason than they are still path dependent on their old silly questions and frames of reference.

You will have become an innovator without peer.