It was a Monday. I don’t think I made a very good impression that day. I was only a few weeks into my new role as the head of a team that had been together for quite while. I recall the day because of the look one gentleman in particular gave me after a comment I had made. It was as if I had crushed his dream. What I said was right, but that didn’t seem to matter. I still crushed his dream. With two simple words, I also dented a number of other ambitions, as well.

It was a Monday. I don’t think I made a very good impression that day. I was only a few weeks into my new role as the head of a team that had been together for quite while. I recall the day because of the look one gentleman in particular gave me after a comment I had made. It was as if I had crushed his dream. What I said was right, but that didn’t seem to matter. I still crushed his dream. With two simple words, I also dented a number of other ambitions, as well.

The words “Meets Min,” short for “meets the minimum requirements,” is not an aspirational phrase. There aren’t any motivational posters praising the emotional excitement of doing only that which is absolutely required. Yet, that is the advice I had given Steve that threw him into a tailspin.

Steve was a reach for the stars kind of guy. His dreams were big and everything he wanted to accomplish was larger than life. He wanted to make people’s lives better. He put everything he had into everything he did, which is precisely what kept him from accomplishing what he dreamed. Dreams can get in the way of a dream.

I consider meets-min a critical component of big dreaming. That big dream you have is going to take a lot of time and energy. Anything that doesn’t contribute to that dream must be considered a distraction. Unfortunately, those distractions may be necessary. The way you balance distraction and necessity is through meets-min. What is the least you can do to accomplish the minimum requirements of that distraction so that you can put more time and energy into the one big thing that will propel you above the rest?

Greg McKeown, author of Essentialism, calls this one big thing your essential intent. McKeown advocates that we are better served moving a mile in one direction rather than moving an inch in a thousand different directions. I wholeheartedly agree. It requires, however, going through a tough process of determining what defines your essential intent or single vision dream. We’ll discuss how to do that another time, or if you can’t wait, go buy his book. Without knowing your essential intent, you can’t know what to stop doing or when to apply meets-min thinking.

Greg McKeown, author of Essentialism, calls this one big thing your essential intent. McKeown advocates that we are better served moving a mile in one direction rather than moving an inch in a thousand different directions. I wholeheartedly agree. It requires, however, going through a tough process of determining what defines your essential intent or single vision dream. We’ll discuss how to do that another time, or if you can’t wait, go buy his book. Without knowing your essential intent, you can’t know what to stop doing or when to apply meets-min thinking.

I remember when a coworker of mine was reporting the incredible success he had in developing our relationship with a governmental compliance agency. He told our COO, Doug, that we were considered a model company by that agency and that the agency was extremely pleased with how well we worked with them. Our COO snarled a bit and said, “I don’t want to be that good. We just have to be good enough to get the check box for compliance. Anything more is a waste of your very valuable time.” In Sopranos parlance, Doug had just ordered a meets-min hit.

McKeown believes that leaders should be thought of as Editors-in-Chief. A leader’s chief role is to remove all the work that is non-essential so that team members can put more energy into their essential intent. Their job is deciding what is not important. Did you know the root of the word decide is the latin word cid which means to kill. The process of deciding is an act of killing all that is unnecessary until you reach the one important thing. Doug was a great Editor-in-Chief. He was constantly asking questions that caused his teams to reassess if what they were doing was necessary.

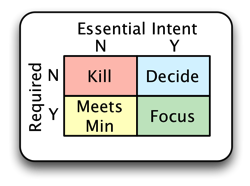

I’ve developed a 2×2 that I use to assess how I should respond to the flurry of things that “need” to be done. One axis represents whether a task is part of your essential intent. The other axis defines if the task is mandatory. In order to work this matrix, you have to be completely honest on whether something is essential and whether it is required. It’s very possible you may think something is required simply because you like doing it. This is where most will fail.

Two of these quadrants are easy. Focus your efforts on the those things that contribute to your Essential Intent AND are required, then stop doing those which are neither. Those things that you are required to do but don’t fit into your essential intent require a meets-min position. Do only the bare minimum to meet these mandatory requirements.

It gets a bit more difficult to decide what to do with those things that contribute to your essential intent but are not required to perform. The best action here is to decide which of  these tasks give the greatest contribution to your essential intent, and rank them in order of contribution/effort. As you reclaim time from those tasks you are now killing or giving the ole’ meets-min to, you can now apply that time to taking on tasks from the Decide quadrant. These optional tasks might contribute nicely to your essential intent, but would have otherwise been ignored if you hadn’t reclaimed time from the other two quadrants.

these tasks give the greatest contribution to your essential intent, and rank them in order of contribution/effort. As you reclaim time from those tasks you are now killing or giving the ole’ meets-min to, you can now apply that time to taking on tasks from the Decide quadrant. These optional tasks might contribute nicely to your essential intent, but would have otherwise been ignored if you hadn’t reclaimed time from the other two quadrants.

Since that initial meets-min conversation with Steve, I mockingly call this 2×2 matrix the Dream Crusher. It’s hard to say no to things that you would like to do. It’s hard to only do the bare minimum, especially if you are known as an over-achiever. Steve eventually understood that by not giving 100% to everything, often giving 0%, we actually get to our dream state faster.

I find using the Dream Crusher helpful as it forces me to explicitly state my essential intent and then to determine if something is truly required or not. It also creates a healthy framework between my boss and me when it comes down to deciding how much energy should be spent on a task and why. Most importantly, when I know that my energy is aligned with what is truly important, I can go home at night and feel good about what I had accomplished that day.